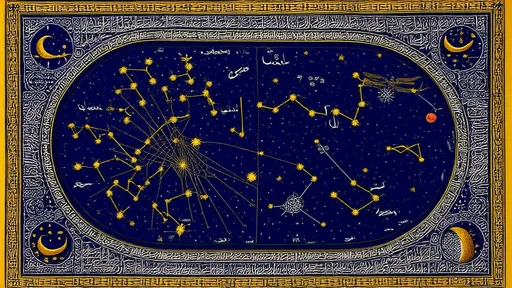

The art of celestial cartography has long been a bridge between science and aesthetics, and nowhere is this more evident than in the exquisite tradition of Persian astronomical embroidery. These intricate star maps, painstakingly stitched onto textiles, represent a unique fusion of mathematical precision and artistic expression that flourished particularly during the golden age of Islamic astronomy between the 9th and 15th centuries.

What makes these embroidered charts remarkable is their dual function as both scientific instruments and devotional objects. Persian scholars didn't merely record celestial patterns; they transformed them into visual poetry. The famous Zij-i Sultani star tables, originally compiled by Ulugh Beg in the 15th century, found their way onto ceremonial textiles where constellations were rendered in silver thread against deep indigo backgrounds, their positions verified through observations from the Samarkand observatory's massive sextant.

The materials themselves tell a story of cultural exchange. Chinese silk formed the foundation for many of these works, while Indian gold thread and Byzantine dyeing techniques contributed to their luminous quality. A particularly stunning example resides in the Museum of Islamic Art in Doha - a 13th-century prayer rug from Shiraz featuring the complete northern celestial hemisphere, with each star's magnitude carefully indicated by the size of seed pearls sewn into the textile.

Beyond their astronomical accuracy, these embroideries embed layers of symbolic meaning. The recurrent motif of the Pleiades cluster (known in Persian as Parvin) appears not just as a celestial marker but as a poetic reference in the woven verses of Hafez and Rumi that often border these star charts. This intertwining of science and literature reflects the Persian concept of jam-e jam, the mythical cup that revealed cosmic truths through both calculation and contemplation.

The production process itself was a ritual. Master embroiderers, often working in royal workshops attached to observatories, would begin their work during auspicious planetary alignments. The positioning of certain constellations relative to the textile's edges frequently corresponded with qibla orientation, transforming these star maps into spiritual compasses. A surviving manuscript from Herat describes how artisans used astrolabe projections to transfer coordinate grids onto fabric before any stitching commenced.

Modern scholarship has revealed the remarkable accuracy of these textile star charts. When researchers at the University of Tehran digitally mapped the stellar positions on a 14th-century Isfahan embroidery, they found the coordinates matched Ulugh Beg's calculations to within 0.5 degrees - an astonishing precision considering the medium. This challenges our assumptions about the separation between "scientific" and "decorative" arts in medieval Islamic culture.

The tradition persists today in modified forms. In Yazd, a group of female artisans continues to produce embroidered star maps using patterns descended from Safavid-era originals. Their contemporary works incorporate the orbits of modern discovered planets while maintaining the distinctive Persian aesthetic of representing Jupiter as a turquoise-studded disk and Mars as a crimson teardrop shape. This living tradition serves as a testament to the enduring power of combining cosmic wonder with textile artistry.

Recent exhibitions at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Louvre Abu Dhabi have introduced these astronomical textiles to wider audiences, prompting reevaluation of their significance. No longer seen as mere illustrations of scientific concepts, they are now understood as a distinct genre where the very act of embroidery - the passing of thread through fabric - mirrors the celestial motions they depict. The warp and weft become coordinate lines, the stitches transform into stars, and the completed work emerges as both map and meditation.

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025